The proliferation of infecting bacteria that have developed resistance to antibiotics is causing a global microbiological crisis.

On September 21, 2016, the UN General Assembly convened to discuss the problem of pathogens that develop antibiotic resistance. They deemed the problem of harmful microbes with antibiotic resistance genes to be “the greatest and most urgent global risk.” This crisis is causing molecular biology researchers to once again explore the use of viruses as medical tools.

Their medical research revealed so many different bacteria-eating viruses in our world that many of them have to emerge as allies in our battle against antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

What is a bacteriophage?

A virus that eats bacteria is called a bacteriophage, or just “phage” for short. Phages visually resemble a cross between a lunar landing module and a filamentous tarantula, all reduced to microscopic size.

The number of bacteriophages that exist in the world at the very moment you are reading this is staggering. Or maybe astounding is the better word. You decide, after learning that 1/5 of a teaspoon of ordinary seawater contains at least 50 million phages. If each phage were the size of a small beetle, the world would be covered in bugs to a uniform depth of several miles. (Good luck letting go of that image.)

Note that we’re discussing the sort of virus that eats bacteria

While many bacterial strains are beneficial to humans, others cause deadly infectious diseases. The science of virology has long known about viruses that are bacteria eaters. So why hasn’t medical research utilized bacteria-eating viruses to eradicate harmful infections?

What is the history of bacteriophage therapy

Medical researchers made progress down that path about 100 years ago. Two scientists (a Brit named Frederick Twort and Felix d’Herelle, a French-Canadian living in Paris) independently discovered that many viruses destroy bacteria in the process of replicating themselves.

But the medical techniques and equipment then available limited the use of phages as therapy. Although some good outcomes were achieved, the results were inconsistent. When antibiotics were discovered in the 1940s, bacteriophage research was relegated to a few practitioners in the former Soviet Union, particularly Georgia and Poland.

However, the current spate of widespread antibiotic-resistant bacteria, impervious to even the newest types of antibiotics, is causing resurgent interest in phage therapy and research.

Recent use of phages with a life-saving outcome

The patient had undergone a double lung transplant. Shortly after the procedure, the patient incurred an intractable infection, caused by bacteria that were resistant to all varieties of available antibiotic medication.

After a search that lasted months, a bacteriophage was found that feeds on the bacteria infecting the patient. A series of doses, each containing more than a billion phages, boosted the patient’s immune system and caused the infection to practically disappear.

How do bacteriophages work?

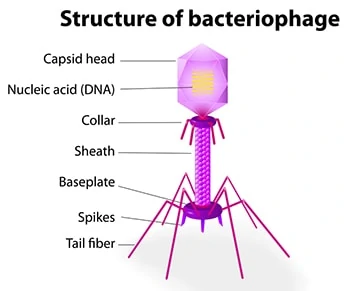

The phage genome is a simple, yet incredibly diverse, non-living biological entity. It consists of DNA or RNA (never both) enclosed within a protein casing. The “non-living” descriptive means that phage genes are incapable of reproducing independently; their lifecycle is ultimately dependent on a new host for survival.

A phage’s nucleic acid is encased in a protein shell, known as a capsid, that protects the phage from being destroyed by enzymes. A phage’s capsid is equipped with external spikes that enable the phage to attack bacteria by attaching to receptors on the bacterial cell’s surface.

There are two types of bacteriophage, temperate phages and lytic phages (aka lysogenic phages)

A temperate phage enters into a more or less symbiotic relationship with its bacterial host. But a lysogenic phage begins the process of destroying its host bacterial cell by injecting its genetic material into the host cell.

That nucleic acid then hijacks the bacteria’s replication machinery to produce the next generation of new phage progeny. In this process, the bacterial cell wall undergoes lysis (i.e., it is ruptured and destroyed).

There are a lot of phages. This is an understatement.

The British patient was lucky. There are a trillion trillion trillion trillion trillion (and then add a few more trillions) phages in existence, and most of those phages appear to be genetically distinct from almost every other one. This makes the search for a phage that will initiate the lytic cycle in a particular host bacterium like looking in a cosmic haystack for a microscopic needle.

Several institutions are in the process of developing phage libraries

For example, the Phage Directory, an Atlanta, Georgia, nonprofit, helps to match patients with phages that precisely target their particular infection, including E. coli and staph infections.

When a patient needs phages to treat an antibiotic-resistant infection, an email goes out to dozens of cooperating research labs. The labs then scan their phage collections to see whether any of them have the right phage to attack the patient’s unique bacterium. Once a lab locates a phage of sufficient specificity, technicians grow billions of the viruses and ship them to the treating doctors.

Phages are dynamic and rapidly evolving entities

Phages therefore do not fit easily within current medical categorization and development models.

In this sense phages act as disruptors, revealing the artificial limitations imposed by the existing antibiotic-centric infrastructure.

Developmental problems in the synthesis of bacteriophage therapy

- Phages are difficult to develop, control, and stabilize. These traits require the construction of dedicated production facilities, including clean rooms, where the intrusion of external particles is tightly controlled. This limits the risk of contamination. Temperature, humidity, and pressure levels must also be closely monitored. These kinds of facilities are very costly.

- Another problem that phage producers face is rooted in questions of how ownership of a phage inventory can be established, maintained, and monetized.

Unlike chemical molecules, which can be quite easily patented, phages are natural entities. As such, they are currently not patentable under existing legal structures, whether North American or European. Phage production start-ups are actively searching for contractual solutions to protect their work. - These uncertainties contribute to the difficulties that new phage businesses encounter in their efforts to find, keep, and ultimately reward investors.

- Governmental entities have been slow to join the search for effective phage therapies.

- The nature of the clinical trials presents another problem for the development of phages as weapons against bacterial infections. Every new medical event must undergo clinical trials to demonstrate safety and efficacy.

So when phages are clinically employed against infection, they are usually administered together with the latest advances in antibiotics. This means phages are not given an opportunity to clinically demonstrate their ability to conquer bacteria on their own, without a complementary dosage of standard antibiotics.

Natural-born killers of bacterial infections are too valuable to ignore

The potential benefits of phage therapy are far too great to allow these current difficulties to prevail. We’re confident that microbiology research will eventually learn how to successfully develop these natural-born killers of bacterial infection.

About Dr. Thaïs Aliabadi

As one of the nation’s leading OB/GYN’s, Dr. Thaïs Aliabadi offers the very best in gynecology and obstetrics care, including telehealth appointments. Together with her warm professional team, Dr. Aliabadi supports women through all phases of life. She creates a special one-on-one relationship between patient and doctor.

We invite you to establish care with Dr. Aliabadi. Please click here to make an appointment or call us at (844) 863-6700.

We take our patients’ safety very seriously. Our facility’s Covid-19 patient safety procedures exceed all CDC and World Health Organization recommendations. Masks are required in our office at all times during the coronavirus pandemic.

The practice of Dr. Thais Aliabadi and the Outpatient Hysterectomy Center are conveniently located to patients throughout Southern California and the Los Angeles area. At the Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, we are near Beverly Hills, West Hollywood, Santa Monica, West Los Angeles, Culver City, Hollywood, Venice, Marina del Rey, Malibu, Manhattan Beach, and Downtown Los Angeles, to name a few.